This is part 5 in an ongoing series on gender by Dr. Preston Sprinkle. Click here to see the first post.

What if someone has a female body but a male soul? Are they a man or a woman?

I’m going to wrestle with these questions below. But if you’re just now jumping into this blog series, it’ll be helpful to go back and read the first 4 posts, especially the last 2 (HERE and HERE) where I began our discussion of gender identity from an anthropological perspective. In short, I’m wanting to explore the best anthropological evidence for the claim that one’s gender identity is more ontologically significant than one’s biological sex for determining whether a person is a man/boy or woman/girl, especially in cases where there is incongruence between a person’s gender identity and their biological sex. (“Ontology” simply deals with the nature of being.)

The three most significant pieces of evidence for this claim are:

- one’s self declaration: “I am a boy because I know that I am, I feel like I am, and I therefore am a boy.”

- the brain-sex theory: “While my body is female, my brain is male.”

- the theory of a sexed soul: “While my body is male, my soul is female.”

None of these are mutually exclusive, of course. And they are often all held at the same time, though non-religious people might talk about the feminine essence theory instead of the (3) sexed soul theory.

Let me quickly sum up what I’ve said in the previous 2 posts. While I want to understand, respect, and learn from (1) one’s self declaration, I don’t feel like it’s a sufficient piece of anthropological evidence in itself to determine one’s ontological state. Just because someone says they are _______ doesn’t mean they are ________, and most humans live by this logic no matter how confident and persistent the claim of whatever you put in the blank may be. I never want to underestimate or downplay the psychological and personal significance of (1) one’s self declaration. And I don’t think non-trans people will get very far in a genuine relationship with trans people until they respect the profound power of (1). “Respect” doesn’t mean “agree with,” but it does mean to "genuinely listen to, esteem, and seek your hardest to understand." But as a piece of anthropological evidence, I believe it’s insufficient for determining one’s ontological status as a man or a woman.

My last post explored (2) the theory that one’s brain might be sexed differently than their body. I find this theory to be scientifically lacking and logically misguided for various reasons explored in the post. In particular, the brain-sex theory appears to employ gender stereotypes for the theory to work, which is problematic on so many levels. But again, if I’m missing something, please let me know.

In this post and the next, I’d like to explore (3) the theory that one’s soul/spirit is sexed and that the soul/spirit could be sexed differently (through the fall, or whatever) from their body.

Body and Soul/Spirit

Once we raise the question of the relationship between the soul and the body, we open the door to debates within the discipline of theological anthropology, or “theological reflection on the human person.”[i] What is the soul? How’s it related to the body? Is the soul something metaphysically different from the body? Or are they so intertwined that it’s impossible to untether the two? And a myriad of other questions scholars wrestle with and debate.

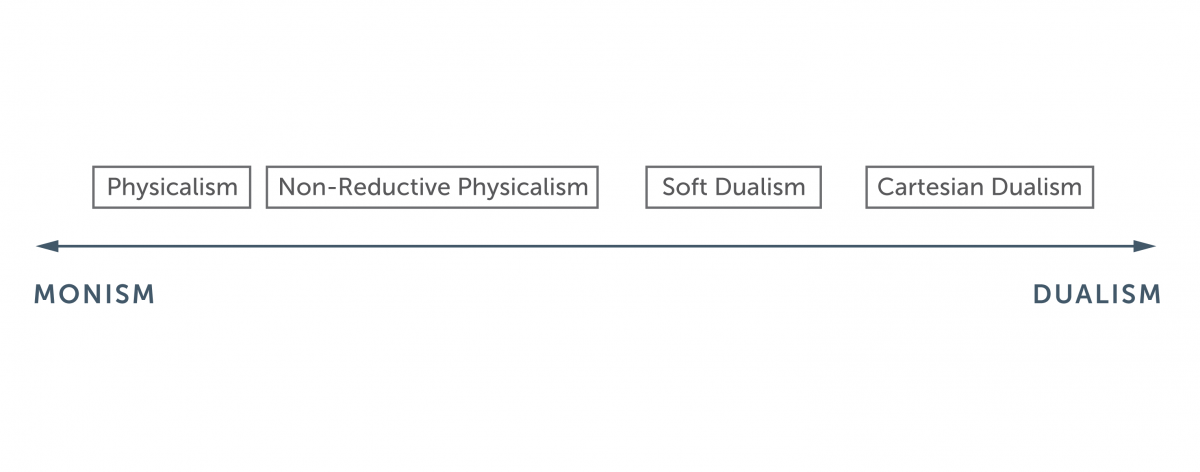

In general, there are a spectrum of views that could be mapped as follows. There are a number of different labels we could use here, and this layout is grossly oversimplified. But it might be a helpful heuristic picture for those who aren’t familiar with discussion.

Those on the left emphasize monism (unity of human nature), while those are the right emphasize dualism (division in human nature).

Or more thoroughly:

- Physicalism says there is no spirit/soul, or no immaterial part of you. All the stuff that seems immaterial can be explained by neurology. Your emotions, your imagination, your will—they’re all byproducts of that material thing called the brain.

- Non-Reductive Physicalism says there is an immaterial part of you, but it’s inextricably bound to your embodiment. While our existence can’t be reduced to our physicality, neither can it be considered apart from our physicality. There is no body/soul distinction, only ensouled bodies or embodied souls.[ii]

- Soft-Dualism upholds the importance of the body and embodiment for personhood, but argues that soul and body are “two ontologically distinct substances that are conceivably separable.”[iii]

- Cartesian Dualism (from Rene Descartes) says that “the spiritual and the physical are two, fundamentally distinct, ‘parts’ of the human person” and typically views the immaterial as much more central to who we are than our body. Extreme versions might even denigrate the body as worthless and evil.

We can quickly nix the first view, Physicalism, since it’s not a Christian view. It assumes that there is no God, no Creator, no Spirit or spirit. Virtually every Christian thinker agrees that pure, grade A Physicalism is not taught in Scripture. The last view, Cartesian Dualism, is also not a Christian view—despite widespread support from old hymns and the popular imagination of many Western Christians (“like a bird from prison bars has flown, I’ll fly away”). Marc Cortez, a renown expert in theological anthropology, rightly says: “Nearly everyone affirms that human persons are physical, embodied beings and that this is an important feature of God’s intended design for human life.”[iv]

Now, you may think that this settles our question. The “soul sexed differently from the body” view is straight up Cartesian and therefore not a serious Christian option. I used to think the same thing, that the “male body, female soul” theory was anti-body and therefore anti-Christian. And honestly, when I read statements from some trans or trans affirming writers, it sure sounds like their quoting Descartes—if not ancient Gnostic texts. Some “born in the wrong body” beliefs, as if the real you is disembodied, smacks of Cartesian dualism and is therefore not a Christian view of human nature. But not every trans person actually likes the “born in the wrong body” language.[v] While some have used it to describe their experience or how they feel, this doesn’t necessarily mean they are using it as an anthropological declaration.[vi]

In any case, Cartesian dualism isn’t the only anthropological model that’s necessary for the “sexed soul” theory to work. I think it is theoretically possible for someone to hold to a soft-dualism and use that has a framework for arguing that someone could have a soul that is sexed (or gendered) differently than the body. (Yes, I’ll discuss below whether it’s valid to even talk about “sexed souls.”)

Soft Dualism and a Sexed Soul

Again, soft dualism believes that the “mental and physical realms are both fundamental”[vii] to human nature and that “these two parts are fully integrated and interdependent such that the organism as a whole functions properly only when both are working in intimate union.”[viii] And yet the “mental and physical realms are ontologically distinct” and “can (at least) conceivably exist separate from the other.”[ix] (By the way, scholars often use “mental” interchangeably with “soul,” “immaterial,” or “spirit.”) Justification for this view comes from the doctrine of an intermediate state; namely, that the soul can be temporarily separated from the body at death and prior to resurrection, in which case “you” still exist apart from the body, albeit temporarily.[x]

One could argue, therefore, that (through the Fall, or whatever) in some cases one’s soul is misaligned with their body.[xi] This, of course, would raise the question: Is the soul or the body more ontologically significant for one’s status as male or female, when there’s incongruence?

While the “male soul, female body” theory is possible and could draw upon a soft-dualistic perspective (a legitimately Christian view to hold) I find this view problematic for several reasons.

Now, let me be honest with you. I’m not an expert in theological anthropology, nor do I claim to have this part of the conversation all figured out. I very well could be missing a vital piece of evidence or knowledge that I’m not aware of. (And if you are aware of this knowledge, please do share the wealth!). In any case, here are some problems I have about the aforementioned view.

First, non-intersex bodies are clearly sexed. But are our “souls” sexed? To repeat what I pointed out in my first post, “[A]n organism is male or female if it is structured to perform one of the respective roles in reproduction” and “[t]here is no other widely accepted biological classification for the sexes.” In other words: the categories of “male” and “female” are, by definition, descriptions of our bodies and not our souls or the immaterial aspects of our being.

This doesn’t mean that our femaleness and maleness don’t affect the immaterial aspects of our lives. Of course they do. Sex hormones, for instance, have at least some effect on our thoughts and our emotions, and our social interactions as males and females shape our “inner selves” (whatever we mean by that phrase). But we don’t determine whether a non-intersex person is male or female based on the immaterial aspects of ourselves, since male and female aren’t immaterial categories. Any disagreement with this would have to employ the categories of “male” and “female” in ways that go against the “widely accepted biological classification for the sexes.”

Second, even proponents of soft dualism are nervous about pitting the soul against the body in some kind of hierarchical fashion. To do so would be right at home with Cartesian Dualism, if not Gnosticism. In other words, even if the immaterial aspects of personhood might be conceived as ontologically distinct entities, we can’t therefore assume that the soul is more definitive of personhood than the body in cases where there is incongruence. Soft dualists are still wanting to maintain the psychosomatic (soul-body) unity of the person, where the material and immaterial aspects of human nature are equal and integrated, even if they are ontologically distinct. Even if a person’s soul was sexed differently than their body, this wouldn’t automatically mean the soul overrules the body, especially if the non-intersex person is 100%, verifiably, without a doubt male or female. Can we say the same thing about the male or female status of someone’s soul? What evidence would you use to prove that someone's soul is male or female? Try to do this without appealing to gender stereotypes.

Third, there’s a widespread misunderstanding of what the soul even is. It’s unfortunate that when we see the word “soul” next to the word “body,” virtually every Westerner thinks “immaterial” or “non-physical” when they see the term “soul.” Plato would certainly agree with this, but I’m not sure the Bible does. Biblically, Hebrew and Greek words translated “soul” are much more material than we often think.

Take the Hebrew word nephesh, for instance. Nephesh is the main word lying behind the English word “soul,” but it’s also translated as “life,” “person,” “breath,” “inner person,” “self,” “desire,” or “throat.”[xii] Nephesh is even used in reference to the “souls” of animals (e.g. Gen 1:24; 9:10), which—unless you’re that kind of animal lover—throws a wrench into most people’s view of the “soul” as something uniquely human. In the Old Testament, “nephesh is used with reference to the whole person as the seat of desires and emotions, not to the ‘inner soul’” as some immaterial aspect of human nature as Plato would have it. In a lengthy study of nephesh, Edmond Jacob concludes: “Nephesh is the usual term for a man’s total nature, for what he is and not just what he has…Hence the best translation in many instances is ‘person’.”[xiii]

The same goes for ruach, the Hebrew word for “spirit.” We don’t need to get into the details, since it’s not really disputed among biblical scholars. But “ruach…must not be thought of as a separable aspect of man, but as the whole person viewed from a certain perspective.”[xiv]

Greek words for “soul” or “spirit” reveal similar polysemy (“many possible meanings”). Psyche, for instance, is often translated as “soul” and on a few occasions can refer to immaterial aspects of a person. But it rarely, if ever, refers to the immaterial part of a person in contrast to the material part. Psyche, like nephesh, “often stands for the whole person”[xv] not just the immaterial part of you, as in the following:

- “Then fear came over every soul” (psyche) (Acts 2:43)

- “And every soul (psyche) who will not listen to that Prophet will be completely cut off from the people” (Acts 3:23)

- “In [Noah’s ark], a few—that is, eight souls (psyche)—were saved through water” (1 Pet 3:20)[xvi]

Along with referring to the whole person, psyche (like nephesh) can actually be used to refer to many different aspects of human nature, such as the “life” of a person (Rom. 11:3; Phil 2:30; 1 Thess. 2:8) or our “emotions” (Mark 14:34; Luke 2:35; used of God’s emotions in Matt. 12:18). On at least one occasion, psyche refers to an aspect of embodied life that might survive death, as in Matthew 10:28: “Don’t fear those who kill the body but are not able to kill the soul; rather, fear Him who is able to destroy both soul and body in hell.” This statement borders on a more Platonic understanding of the soul as the part of “you” that survives death but won’t survive in hell. (And all the annihilationists said…Amen!). It would be odd, I think, for Jesus to side with Plato rather than with His own Hebrew Scriptures. So perhaps the phrase isn’t as Platonic as it may seem—pitting the soul, as the superior immaterial part of you, up against the body. It’s quite possible, some would say likely, that psyche here simply refers to one’s true life as opposed to one’s earthly life only, as it does in other passages (Mark 10:45; Acts 20:10).[xvii]

But even if you think Matthew 10:28 is a slam dunk in favor of soft dualism, you’d still have to acknowledge (because it’s a plain fact) that Greek and Hebrew terms for “soul” are polysemous and often refer to material aspects of human nature. New Testament scholar Joel Green sums it up well when he concludes:

Given this polysemy [of words translated as “soul”], we would be mistaken to assume that the word psyche…actually means “soul” (or requires an identification with the concept of “soul”), defined as the spiritual part of a human distinct from the physical or as an ontologically separate entity constitutive of the human “self.”[xviii]

Many scholars come to similar conclusions as Green’s. “Recent scholarship has recognized that such terms as body, soul, and spirit are not different, separable faculties of man but different ways of viewing the whole man,” writes biblical scholar George Eldon Ladd.[xix] And Mark Cortez says this this understanding of the “soul” is one of the things that Christian scholars across the anthropological spectrum agree on, that “‘soul’ does not refer primarily to the immaterial essence of a human person but to the whole human person as a living being.”[xx]

(Tentative) Conclusion

Now, I don’t want to get too far down the rabbit hole of word studies and which scholar believes what. I only want to make three modest points that I think any serious Christian thinker who’s dabbled in theological anthropology would agree with.

1. We simply cannot assume that the Bible teaches some kind of immaterial part of “you” called the soul or spirit or whatever as some ontologically distinct aspect of human nature that would overrule the body if the two were at odds. I’m not saying such an argument can’t be made. I’m only saying that an argument (not an assumption) needs to be made. Simply affirming a “female soul, male body” narrative without justification is either lazy or uninformed.

2. If you were able to present a convincing case that one’s soul/spirit is an ontologically distinct aspect of human nature, then you’d still have to show that the soul/spirit is sexed or gendered. Now, since “sex” is, by definition, a bodily category, we can’t legitimately talk about a “sexed soul” as an immaterial part of you that’s distinct from the body. We’d have to talk about a “gendered soul,” not a “sexed soul.” But—we’d then have to establish what we mean by “gender.” As we’ve seen in my first few posts, there’s not a lot of consensus on what people even mean by “gender,” and many ideas about gender are entangled with cultural stereotypes. Again, I’m not saying that a case can’t be made. I’m only saying that it’s going to take a bit of work to argue for a “female soul, male body” without relying upon 20th century, patriarchal theories about what constitutes femaleness and maleness.

3. We’d then have to show that the “male soul, female body” view makes more sense than the alternatives. One of which would say that humanity is an integrated whole where there is no hierarchy between the material and immaterial. All non-intersex humans are either male or female, which are determined by their bodies. Such non-intersex persons might experience incongruence between their immaterial aspects (heart, soul, spirit, mind, will, etc.) and their embodied selves, which are either male or female. But if there’s incongruence between the immaterial (mind, soul, etc.) and material (body), this doesn’t circumvent one’s objectively verifiable status as either male or female.

I want to unpack this view in much more detail in a later post. But first, I feel the need to (finally) discuss the beautiful, image-of-God bearing, and often misunderstood portion of the population known as intersex persons.

[i] Cortez, Theological Anthropology, 5.

[ii] This view became prominent in biblical scholarship in the mid-20th century through the work of Rudolph Bultmann, who famously said: “Man does not have a body; he is body.” Many other scholars have argued for some kind of non-reductive physicalism since Bultmann including J. A. T. Robinson, F. F. Bruce, Brevard Childs, K. G. Kümmel, Anthony Hoekema, Joel Green, and many others. Joel Green boldly observes: “a constellation of issues and concerns has coalesced in biblical studies over the last century with the result that theories of body-soul dualism are today difficult to ground in the Bible” (Body, Soul, and Human Life, 22). One of these issues Green refers to is the development of neuroscience in recent years.

[iii] Cortez, Theological Anthropology, 73. Some recent proponents of this view (or a version of it) include Scott Rae, J. P. Moreland, John Cooper, and William Hasker.

[iv] Cortez, Theological Anthropology, 70.

[vi] Others resist the common assertation that all trans people are modern Gnostics since they deny their bodily reality. Trans writer Christina Beardsley says that those who pursue sex reassignment surgery are not on a quest toward “a Gnostic rejection of the body, or a denial of its importance, but a quest for fuller embodiment” (This Is my Body, 75). I’m not sure if this completely alleviates the Gnostic allegations, since “a quest for fuller embodiment” through surgery is, in a sense, a rejection of the body you were born with—or more accurately: the body that is you. The point is, we need more conversations that truly seek to understand what someone else actually believes and less labels toss around that simplify complex issues.

[vii] Cortez, Theological Anthropology,72.

[viii] Ibid., 73.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Non-reductive physicalists respond to this argument in various ways. Some will deny that there is such a thing as an intermediate state where people exist in some kind of disembodied state. Others say that if there’s a disembodied intermediate state, it’s the exception to the rule and not the norm. Our earthly life is embodied. Our resurrection life will be embodied. These book ends of our existence should be the primary lense through which we understand human nature in the here and now.

[xi] For an informed argument in this direction, see https://www.thoughtstheological.com/a-female-soul-in-a-male-body-a-theological-proposal/

[xii] Green, Body, Soul, and Human Life,54.

[xiii] Theological Dictionary of the New Testament,9:620 cited in Hoekema, Created in God’s Image, 210.

[xiv] Hoekema, Created in God’s Image,211.

[xv] Ibid., 213.

[xvi] See also Rom. 2:9; 13:1

[xvii] R. T. France understands psyche in this passage in the sense of “true life” (Matthew, 403).

[xviii] Body, Soul, and Human Life,57.

[xix] A Theology of the New Testament, 457, cited in Hoekema, Created in God’s Image,210.

[xx] Cortez, Theological Anthropology, 70.

Comments

The spirit is willing...

Hi Preston,

The verse that talks about “the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak” would have me believe that spirit/soul and body are different things. What are your thoughts?

Also, in the resurrection, aren’t we given new bodies? Will those bodies be gendered? Jesus (or was it John in Revelation?) said there’d be no marriage in heaven. If no marriage, and thus no sex leading to procreation, will gender even be included in our new bodies? Angels apparently don’t have gender, if I’m remembering correctly.

Spirit/soul and body

Hey Dayna, great questions!

My point is not that there aren't immateiral aspects of human nature, and that those immateiral aspects are sometimes called "spirit" or "soul." My point (probably not spelled out very clearly) is that the various biblical terms used to describe the immaterial parts of humanity are used in a varieity of different ways and that when they do refer to the immaterial aspect of human nature they typically don't have a soul VERSUS body meaning, but refer to humanity as an integrated whole. With the verse you referenced, we also have to understand that the term "flesh" is also used in a variety of different ways. In Paul's letters, it typically means our sinful impulse, not the physical flesh covering our bodies. So that verse could express the immaterial/material dichotomy that you suggest. Or it could express the moral tension we feel as Christians between the propoensitiy to do bad (the flesh) vs. the propensity to do good (the spirit). Or something along these lines.

Matt 22 talks about no marriage in the resurrection but there's no evidence that our resurrected bodies won't still be sexed and various passages that suggest they will be sexed (1 Cor 15 and others). Our male and female sex differences are just about marriage; single people are still male and female, so even if there's no marriage in the resurrection, it doesn't follow to say that THEREFORE there won't be any sex differences.

Angles and gender. That's a tough one. Whenever angels appear in the Bible, they apear as men and the one's that are named are given male names.

Hope that helps!

More questions and foundational anthropology

Hey Preston, great summary (as with all these blogs so far) and good distinctions on some tricky terms etc. Again this has raised lots of healthy questions for me. A big question is what is our underlying, foundational, anthropology? What do we build being human on and what do we build being male and female on?

Biology is playing a big part in what you've written, understandably, in defining a person as male or female. The observable aspects of one's body determining one's biological sex makes sense. I do wonder, whether this is too reductionist? It might not be, but being male or female is ultimately about more than being male or female (if you catch my drift?). Having all the male bits, makes me male biologically. Beyond biology, what makes me male and whether i feel male are much harder areas to work out (as you've acknowledged).

What does biology give us apart from category terms to separate one group from another? This is of course an important distinction but is biology the bedrock foundation we build off? I may have missed something in the argument, but if biology is the baseline then our anthropology is determined by biology. In time, if we discover biology reasons for one being trans than, biologically, we can say someone is trans. That might be where we feel happy to go. But do we do that with other areas? I might be attacking an argument you've not been making, if so i'm sorry and shoot me down.

Would a better foundational anthropology be 'we are creatures made by a creator, in a fallen world'. We receive our bodies, the good, the bad and the ugly. As we grow we experience pain, discomfort and uncertainty (especially in examples of some trans people, those with body dysmorphia and in puberty - not to conflate the three at all). We are simultaneously coming to terms with a fallen creation, while looking forward to an eschatological hope. This life is therefore uncomfortable and we should seek to care for people as best we can (pastorally, doing whatever seems appropriate to support others). But, also recognising that there is a day coming that we will be at home with our bodies.

That might be all too fluffy and woolly. But those are my best thoughts after only one cup of coffee.

Great questions!

David, I don't know if I have all the answers, but I can easily say that I think you're asking the right questions. It's these kinds of questions that I'm wrestling with.

You ask: "What does biology give us apart from category terms to separate one group from another? This is of course an important distinction but is biology the bedrock foundation we build off?"

Or, as I hear you saying, is being male or female simply reduced to our procreative roles? I would say no; it goes beyond that. For instance, sex differences are celebrated and maintained in passages where procreation is not in view (1 Cor 11 and others). Biologically, of course, our maleness and femaleness, while DETERMINED by our respective structures of reproduction, AFFECTS aspects of our whole being that aren't just about reproduction. Most blatantly, sex-hormones, which are related to (and formative of) our reproductive structures has many affects on our thinking and behavior. Or even from a social standpoint, as males and females form communities, this shapes how we view ourselves and others as male and female.

So, our male and female identities are tangled up with a whole web of personhood; they are not mere "biology," even if those identities are determined by biology. But I don't want to use the word "biology" in a way that makes it sound like I'm downplaying it ("it's just biology," etc.). I prefer the term embodiment.

Also, our male and female embodied identities (and some intersex people might have both) are connected to the "image of God" in us (Gen 1:27), which of course raises lots of questions. The one thing that seems pretty clear is that our embodiment is essential to our reflection of God's image. The very term image is used of "idols" elsehwere: tangible representations of the intangible. And our male and femaleness (again, which includes intersex persons) is wrapped up in how we image God.

What does this look like? Are there certain female bahviors or roles that males should not engage in (besides sexual relations and roles in procreation), and vice versa? I'm still working through all of this.

Image of God and embodiment

Hi Preston, image of God is a more foundational anthropology for me, it is the thing that differentiates humans from animals. Humans are image bearers. God makes his image bearers male and female (and we are aware of intersex persons). I think biology is essential for determining humans as male, female and intersex. Image of God is essential for determining humans as human. It might sound like i'm splitting hairs on this but i think image of God must be our foundational anthropology and then male and female. We image God as humans, embodied humans and sexed humans. I think the questions around male and female behaviours and permissibility are important but i wonder sometimes if we've elevated male and female and demoted image bearer? The classic John Piper question is what do you tell a five year old boy when he asks you what it means to be a man not a woman? The question has significance but actually i think it's missing a first question. What does it mean to be an image bearer? Then what does it mean to be an image bearer who is a man? The second question is not inseparable from the first. When we look at Jesus we're told he is the perfect image of God, not the perfect image of maleness. Image bearing is primary.

Gender identity

My mum has repeatedly told my 3 sisters and I that we're just like our father, but we're not biologically "male" like our dad, so we don't self-identify as "male," "father," "uncle," and "uncle." My sisters and I can all recognise that we have our dad's personality and mannerism, as well as his masculine traits including taller than the average height of a male; larger body structure as males; physically strong in order to do farming work like boys/men and we would wear boys clothes on the farm; played sports with boys; we had to compete against boys in science and maths. My great-grandmother had a beard and a moustache, but she didn't identify herself as my great- grandfather. The new idea that a "boy can have a period" would be drawn the same as a "girl having a period," as well as a "man being pregnant" would be drawn the same way as a "woman being pregnant." However, my husband and son can never experience this type of "boy" nor "man" as they have never had a period and can never experience pregnancy. I have experienced a period and pregnancy, but I don't identify myself as this type of "boy" and "man."

Several points in response

If sex is defined in a strictly biological sense, then the concept can only be applied to biological topics. Sure, biological sex is defined biologically. But this is a matter of how Preston has defined the term, and thus it is circular reasoning for him to turn around and use that definition as if it proves that one’s biology determines everything.

I find it unhelpful to make a strict separation between sex and gender, especially if one believes (as Preston and I seem to agree) that one’s body and soul forms an integrated whole. To talk about a person having a female soul but a male body is to pit the soul against the body in an unhealthy way. Rather, I find it more helpful to say that a person whose gender identity is female but whose body is biologically male is an a state of “in-betweenness.” Rather than saying that such a person is ontologically female, it seems sufficient to say (as you concede can be the case for physiologically intersex people) that their ontological sex is unclear.

I find the discussion of dualism and physicalism to be beside the point. In either case, surely we can agree that the Bible does teach that there is an immaterial part of you. I don’t care whether you call it the soul, or the spirit, or whether you see the soul as comprising both it and the body, nor do I care whether it is “ontologically distinct”; we should at least agree that it exists. The relevant question is then: What happens if the immaterial part of you gives testimony about sex/gender that is at odds with the testimony of your body? Preston seems more interested in disallowing this question than in answering it.

As for the question of whether the immaterial part of you can have any testimony at all about sex/gender, I am frankly surprised that Preston seems to argue that it cannot. Why would Scripture talk about differing gender roles among God’s people if our gender did not have an aspect that is meant to resonate with our immaterial being? On a more practical level, I place a great deal of value on the testimony of our friends with consistent lifelong gender incongruence. The very fact of their experience seems to me to be a strong argument in favor of the claim that gender finds some expression in the immaterial part of you that is complementary to how it is expressed within the body.

Finally, Preston seems to set too high a bar for proof. In order for a view to be considered acceptable within the Christian community, isn’t it enough to show that it is a valid Christian view? If a theory is in reasonable agreement with what we observe, and is not contrary to Scripture, then it should be considered acceptable even if some (like Preston) may not be convinced that it is the best view. Personally, better accordance with facts on the ground is the decisive factor that causes my view to make more sense to me, with a complementary role of course being played by the fact that it is in accordance with Scripture.

Response to Ezekiel

Hey Ezekiel!

Thanks for your thorough response. You raise many good questions and make several interesting points. I appreciate you taking the time to respond to my post. There are several things to discuss here, so let me try to address some particular points.

You said: “If sex is defined in a strictly biological sense, then the concept can only be applied to biological topics. Sure, biological sex is defined biologically. But this is a matter of how Preston has defined the term, and thus it is circular reasoning for him to turn around and use that definition as if it proves that one’s biology determines everything.”

Here, I’d point you back to my first post where I recognized the widely agreed upon definition of sex. It’s inaccurate to say that “Preston has defined the term [biological sex]” in a particular way. I’m simply recognizing the widely agreed upon definition of biological sex. That is, humans are a sexually dimorphic species; they are male or female based on their different reproductive structures. Or as I observed in that first post:

You said: “Sexual dimorphism among non-intersex humans is an established, observable, objective, scientific, “the earth is round and not flat” sort of fact. “[A]n organism is male or female if it is structured to perform one of the respective roles in reproduction” and “[t]here is no other widely accepted biological classification for the sexes.”

Now, you’re free to dispute this “widely accepted biological classification.” I would only need evidence for your disputation for your view to be considered convincing. Either way, this isn’t just my definition that I’m assuming in some circular fashion.

Also, you said that I “use that definition as if it proves that one’s biology determines everything.” I’m not sure what you mean by “everything,” but surely this is an overstatement. Everything? Again, my starting point is very basic. Humans are sexually dimorphic (based on the definition above) and male/female are the terms used to describe this dimorphism. This doesn’t mean that our femaleness and maleness don’t affect the immaterial aspects of our lives. Of course they do. Sex hormones, for instance, have at least some effect on our thoughts and our emotions, and our social interactions as males and females shape our “inner selves” (whatever we mean by that phrase). But we don’t determine whether a non-intersex person is male or female based on the immaterial aspects of ourselves, since male and female aren’t immaterial categories. Any disagreement with this would have to employ the categories of “male” and “female” in ways that go against the “widely accepted biological classification for the sexes.”

You said: “To talk about a person having a female soul but a male body is to pit the soul against the body in an unhealthy way.”

Exactly. But I’m not doing this. That’s the argument other people make—the argument that I’m interacting with. I’m not making this up. Just responding to those who do.

You said: “Rather, I find it more helpful to say that a person whose gender identity is female but whose body is biologically male is an a state of “in-betweenness.” Rather than saying that such a person is ontologically female, it seems sufficient to say (as you concede can be the case for physiologically intersex people) that their ontological sex is unclear.”

This might be the crux of our disagreement. You’re using the terms “female” and “sex” in ways that aren’t recognized by the overwhelming majoring of scholars (conservative, moderate, and progressive) in the conversation.

As I explained in my first post, “sex” is by definition a category of biology; it’s about the respective structures of reproduction that a person has in their body. And “female/male” are the typical terms to describe this aspect of one’s ontology. Gender identity—“one’s internal sense of self”—is not part of the criteria for determining whether a person is male or female.

For your theory to work—and it is a theory, one not recognized by the sciences or the Bible—you’d need to come up with a definition of the sexual dimorphism of humans (an established, scientific fact) includes “one’s internal sense of self” in addition to a person’s biological structures of reproduction.

You said: “I find the discussion of dualism and physicalism to be beside the point. In either case, surely we can agree that the Bible does teach that there is an immaterial part of you. I don’t care whether you call it the soul, or the spirit, or whether you see the soul as comprising both it and the body, nor do I care whether it is “ontologically distinct”; we should at least agree that it exists. The relevant question is then: What happens if the immaterial part of you gives testimony about sex/gender that is at odds with the testimony of your body? Preston seems more interested in disallowing this question than in answering it.”

I mean, my entire blog series is focused on answering that very question. Maybe you haven’t read the whole series? My whole endeavor is to explore whether biological sex (post 1) or gender (gender role [post 2] and gender identity [posts 3-5]) are more indicative of who we are, when there’s incongruence between the two. I then looked at how intersex plays into this (post 6), and my last post (post 7) begins to explore what the Bible has to say about all of this.

Dualism and physicalism is actually a significant part of this discussion, and there’s been way too little reflection on this aspect of the conversation. For what it’s worth, I’d encourage you to think more about how theological anthropology is integral to this conversation.

You said: “As for the question of whether the immaterial part of you can have any testimony at all about sex/gender, I am frankly surprised that Preston seems to argue that it cannot. Why would Scripture talk about differing gender roles among God’s people if our gender did not have an aspect that is meant to resonate with our immaterial being? On a more practical level, I place a great deal of value on the testimony of our friends with consistent lifelong gender incongruence. The very fact of their experience seems to me to be a strong argument in favor of the claim that gender finds some expression in the immaterial part of you that is complementary to how it is expressed within the body.”

Again, our “immaterial” aspects aren’t’ categories of “sex.” They might be categories of “gender” (esp. gender identity) but I’ve yet to find anyone in the field who defines biological sex by immaterial categories like “the internal sense of who you are.” I’m assuming that you didn’t read posts 3-5, because those posts were all about immaterial category of gender identity.

You ask: “Why would Scripture talk about differing gender roles among God’s people if our gender did not have an aspect that is meant to resonate with our immaterial being?” Your question about differing gender roles in the Bible is a very good one. I’d first need to know what gender roles you think are affirmed by the Bible. Submission of wives? No leadership for women? Women should stay at home (Titus 2)? No short hair for females and no long hair for men (1 Cor 11)? What “gender roles” do you think the Bible endorses and demands for all Christ followers of all time? In any case, I never said that the immaterial part of us isn’t correlated with gender roles. My entire 2nd post is devoted to gender roles and I showed that this is different from biological sex.

I love what you said here: “On a more practical level, I place a great deal of value on the testimony of our friends with consistent lifelong gender incongruence.” I do too. A thousand times over, I do too. And I said this in post 3. While I too “place a great deal of value” on personal experience, posts 3-5 tried to show why such personal experiences, while incredibly valuable, are insufficient in constructing a theological anthropology, especially with something as foundation as our sexed embodied existence.

You said: “Finally, Preston seems to set too high a bar for proof. In order for a view to be considered acceptable within the Christian community, isn’t it enough to show that it is a valid Christian view?”

I guess that’s one way to spin it. But all I’m doing is asking some really basic questions about the sex/gender conversation and trying to explore a Scripturally informed response to the most salient questions. One of which is: “When there’s incongruence between one’s biological sex and gender identity, which one is more indicative of who we are and (Scripturally speaking) why? So far, for reasons stated in post 7, I lean toward biological sex being more indicative of who we are, when it comes to determining whether a person is a man or woman, for non-intersex humans.

Ezekiel, I really appreciate your response and the time you took to write it. Plus, you’re named after my absolute favorite book in the Bible, so we MUST hang out sometime! But I think it’d be helpful if you went back and read through the entire series. If you’ve already done so, then maybe read it again? I think there are several things in your response that suggest you haven’t really considered (or refuted?) the various points I’ve made along the way. But if there’s something that’s unclear, then that’s on me, not you! In which case, please let me know if I’ve been unclear on things I’ve said along the way.

Response to Preston (2)

You seem to misunderstand my point about biological sex. Everyone agrees that biological sex is defined biologically. I don’t know why you lecture me about sexual dimorphism when I’ve already agreed on that point. I am not “disput[ing] this widely accepted biological classification,” at least not as long as we’re talking about biology.

What I do dispute is the claim that that biological classification is fully decisive regarding the maleness and femaleness of the person as a whole, including their immaterial part. In other words, I question the assertion that a person’s ontological status in terms of maleness and femaleness is entirely determined by their biological sex.

You seem to make this questionable assertion again in your reply, when you deny the possibility that one’s immaterial part could have something to say about whether they are male or female, “since male and female aren’t immaterial categories.” This is puzzling, because we all know that the conversation our society is having about maleness and femaleness has aspects that are not strictly biological (e.g., gender identity). You seem to have ruled that whole conversation to be out of order, before we’ve even begun.

You make the equally puzzling statement that “gender identity is not part of the criteria for determining whether a person is male or female.” What is your evidence for this? Are you merely making a semantic point, that we should say something like “men and women” or “masculine and feminine” rather than “male and female” when we are speaking of how sex/gender is expressed in the immaterial part of a person? This is hardly agreed upon among scholars. For example, Hilary Lips (whom you’ve quoted appreciatively) defines “gender” as “the nonphysiological aspects of being female or male” (p.5 of Sex and Gender). As I’ve said, I think you and I agree that one’s body and soul form an integrated whole, which (to my mind) means that it doesn’t make sense to make a strong distinction between sex and gender. Sure, it’s fine to talk about one or the other if we are talking primarily in physical or immaterial terms, respectively. Nevertheless, a person’s ontological status in terms of maleness and femaleness must be considered as an integration of sex and gender, an integration of the physical and the immaterial; wouldn’t you agree? For this reason, it seems best to speak of “sex/gender” as a holistic expression of how humans are created male and female.

I said: “To talk about a person having a female soul but a male body is to pit the soul against the body in an unhealthy way.”

In response, you said: “Exactly. But I’m not doing this.”

Indeed. I was stating a point on which we agree.

You accused me of having not read your entire blog series, because I commented that you seemed more interested in disallowing the question of what happens if the immaterial part of you gives testimony about sex/gender that is at odds with the testimony of your body. My comment about “disallowing” now seems needlessly inflammatory, and I’ll retract it with my apologies for that reason. Nevertheless, while it’s true that you discuss gender identity in Parts 3 through 5, your approach is mostly to deconstruct the very idea (and, to my mind, the version of gender identity that you deconstruct is more radical than the version I would hold). It seems to me that your answer to my question is that the immaterial part of you cannot give testimony about sex/gender that is at odds with the testimony of your body, at least not in any real sense. Wouldn’t you agree?

The Bible teaches that men and women have different roles in marriage (Ephesians 5) and different roles in the pastoral oversight of a congregation (1 Timothy 2). Surely these differences in role do not spring directly from the physical differences between male and female bodies, and I reject any notion that these differences in role have to do with any difference in capability. Rather, the fact that these differences in role exist must be telling us that our maleness and femaleness influences how the Holy Spirit interacts with our souls. I can’t give much more detail regarding that, as I am reluctant to delve into mysteries that the Scripture does not reveal. Nevertheless, I see here a sound argument that one’s immaterial part does not merely reflect the maleness and femaleness of one’s body, but rather that one’s immaterial part has its own testimony to give regarding one’s maleness and femaleness.

Theological Method

I’m late to the discussion here and have enjoyed reading the exchange between Ezekiel and Preston.

I do find, Ezekiel, that in your reply to Preston, you continue with your idiosyncratic definition of male/female. In fact, you seem to be arguing with yourself. In your first paragraph, you affirm the consensus biological definition of male/female but in the very next paragraph and throughout the rest of your post, you assert that male/female are synthetic categories of material and immaterial aspects of human being. Such a definition of male/female requires support you don’t provide.

Secondly, and not discussed Preston’s reply is your theological methodology. You seem to grant human experience a status equal to Scripture as a source for doing theology. E.g. you conclude your first post saying, “Personally, better accordance with facts on the ground is the decisive factor that causes my view to make more sense to me, with a complementary role of course being played by the fact that it is in accordance with Scripture.”

The “facts on the ground” do not unambiguously reflect God’s intentions. Both the effects of sin and finitude of human understanding make us dependent on God’s gracious intervention for us to know God’s ways and will. We can’t reason back to God’s intentions for humanity from post-fall and pre-consummation experience. Emphasizing human experience as a theological source equal or greater to Scripture is at the root of liberal Christian theology going back to Schleiermacher.

Response to Bruce

Hi Bruce. I appreciate your reply. It is helpful to know how one is coming across to others, and I'm grateful for the opportunity to correct misconceptions.

I do not believe that male/female are synthetic categories, but I do believe that they are attributes of our entire selves, material and immaterial combined. I gave several reasons for this in my last post, so I'm puzzled to hear you say that I have not done so. I would be glad for you to engage with what I said.

Furthermore, I commend to you the reflections of Pastor Steve Froehlich, who has considered this question with more theological sophistication than I possess.

Because I believe that male/female apply to our immaterial selves, I acknowledge the reality of the biological definition of sex while maintaining that it simply does not always tell the whole story. I don't see this as "arguing with myself." Rather, I think Preston and others are assuming that the biological manifestation of male/female is entirely definitive with respect to our immaterial selves, without having actually proven the claim.

I can see that my remark about Scripture and "facts on the ground" was not as clear as it could be. I certainly do not believe that human experience is on equal footing with Scripture when we are doing theology, nor do I believe that we can reason back to God's intentions using anything other than his self-revelation through the Bible. I do affirm that Scripture is entirely inerrant in what it teaches. If the Bible's teaching is clear on a particular matter, then it is definitive. However, there are many questions that are important to us that are not definitively settled by Scripture alone. In such cases, when more than one view is in accordance with Scripture, we are free to use other sources of knowledge to choose among them. I hope this clarifies my meaning regarding the "facts on the ground." I am glad to answer further questions about this.