This is part 4 in an ongoing series on gender by Dr. Preston Sprinkle. Click here to see the first post.

I recently took a test to see whether I had a male or female brain.[i] The test consisted of 30 different questions with multiple choice answers, such as:

What was the last thing that made you cry?

- Death

- Weight gain

- Cute animal videos

- I don’t cry

My masculine mind kicked into gear and I clicked on “I don’t cry.” Or wait, was I just nurtured into believing that I should give that answer since I’m a guy and guy’s don’t cry? Or am I hardwire to cry less than the female species? That darn nature/nurture dilemma! Anyway, next question:

Which of the following snacks appeals the most?

- Ice cream

- Cake

- Baked beans and hotdogs

- Anything fried

These all sound good to me, actually. Does this mean my brain is intersex? Hmmm, if you had a gun to my head, I’d have to go with “anything fried.” Boom! That’s gotta be a manly answer. Next question:

What’s your criteria when shopping for jeans?

- That they look normal

- How my butt looks

- That I get it over with quickly

- How they look with my shoes

I was tempted to go with “How my butt looks,” since I’ve been doing a lot of squats at the gym recently, but a surge of testosterone rushed through my body and I quickly moused over “That I get it over with quickly.” I’m a guy, after all. And all guys hate shopping. Right?

As I answered other questions like how many times a year do I get moody, and am I excited about the Super Bowl or just the half-time show, and—I kid you not—whether I like Downton Abbey, I had to wonder: Do brains come in male and female sizes? And if so, do they really cause certain people to love sports, deep fried anything, and dogs more than cats?

I’ll share with you the surprising results of my brain test. But first, let’s unpack the so-called brain-sex theory.

Brain-Sex Theory

The brain-sex theory says that one’s brain might have its own sex or gender, which in most humans is aligned with their biological sex, but in some people is misaligned. Some people, for instance, might be biologically male but have a female brain (or vice versa).

Theories about the brain extends far beyond the transgender conversation and has a rather twisted history. For centuries, people have suggested all kinds of theories about brain differences among humans. In 1906, Robert Bean argued that there were “Some Racial Peculiarities of the Negro Brain,” which was the title of one of his papers. Bean suggested that brain differences were the reason why “Negroes” (his term, not mine) displayed “an underdeveloped artistic power” and “an instability of character incident to lack of self-control, especially in connection with the sexual relation.” White people exhibited the opposite: will power, self-control, self-government,” and, of course, “a high development of the ethical and aesthetic faculties.”[ii] Aside from being spine-shiveringly racist, Bean’s study was shown to be scientifically flawed shortly after it was published.[iii]

Another victim of brain research has been women. “Seeing that the average brain-weight of women is about five ounces less than that of men…we should be prepared to expect a marked inferiority of intellectual power in the former,” writes 19th century evolutionary biologist George J. Romanes.[iv] This led Romanes to suggest that this is why women get more exhausted during mentally challenging tasks, and it might explain why women display “a comparative absence of originality…especially in the higher levels of intellectual work.”[v] A few decades later, Dr. Charles Dana pointed out that “the brain stem of woman is relatively larger” while “the brain mantle and basal ganglia are smaller.” Dr. Dana does not think that these differences should “prevent a woman from voting” (good call, Dr. Dana), but these brain differences do “point the way to the fact that woman’s efficiency lies in a special field and not that of political initiative or of judicial authority in a community’s organization.”[vi]

So, women with their small brains should still be allowed to vote—liberation!—but they certainly shouldn’t be able to serve in politics. Such was the state of sex differences and brain-research a hundred years ago.

Things have thankfully progressed quite a bit in the last century.[vii] We now know that brain size is irrelevant for intellect, and many older theories about sex differences were products of ideological—and sexist—assumptions, rather than science. It’s rare that a blatantly racist or sexist study on the brain would make it to publication today, though scholars still bemoan what they perceive as “neurosexism” that exists.

In any case, the battle continues to rage among researchers who argue for or against sex differences in the brain. Feminist scholars in particular have shown that sexism is far from dead when it comes to brain-research, and several have meticulously combed through such studies and pointed out that the supposed sex-differences in the brain are overplayed at best and fabricated at worst.[viii] Why feminists? Because differences between men and women have often been exploited to elevate men and demean women. So, when some people cite brain-research to argue that males are hardwired to perform better in STEM fields, for instance, old wounds are scratched open and the ideological hounds are unleashed.

You may remember when Google engineer James Demore got fired for suggesting that males are generally more skilled and interested in STEM fields than females.[ix] Something similar happened to former Harvard president Lawrence Summers, who got raked under the coals for saying that men are hardwired to be better at math and engineering than women, and that’s why Harvard has more men teaching in STEM fields than women.

Regardless of whether Demore and Lawrence are correct—it’s certainly disputed—it raises questions about sex-difference in the brain, and, in particularly, whether there is such a thing as a male brain and a female brain.

We need to leap over several methodological hurdles before we can even answer these questions.

First, researchers aren’t without bias, especially when doing research that has massive social and political implications. “The existence of a ‘value-free science’ is now commonly recognized as a myth,” writes veteran gender scholar Hillary Lips. “A scientist cannot avoid being influenced by the assumptions and agendas of the surrounding culture.”[x] Biologist Anne Fausto-Sterling sums it up well when she writes:

Ultimately, the questions researchers take into their studies, the methodologies they employ, and their decisions about which additional persuasive communities to link their work to, all reflect cultural assumptions about the meanings of the subject under study—in this case, the meanings of masculinity and femininity.[xi]

This is why you should read multiple studies that are performed by researchers across the political spectrum, and even then you should hold your opinions quite tentatively—especially if you’re not a neuroscientist. (Oh, and it doesn’t hurt to check who’s funding the study.)

Second, when it comes to brain-research, we run into the nature vs. nurture problem of neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity refers to “the ability of the brain to change continuously throughout an individual's life.” This means that if a person’s brain looks and acts a certain way, this may be the way nature made it. Or it may be the way nurture shaped it. Various life experiences from sports to music to dancing to taxi driving quite literally rewire and reshape our brains.[xii]

So even if we were able to see clear differences between “male brains” and “female brains,” we’d have to ask the question: did a “male” brain cause someone to act masculine, or did their masculine behavior cause their brain to look “male.” If a male dancer has a brain that looks similar to a female dancer, we’d have to ask: Do their brains look similar because they both have “female brains” or because they are both human dancers? “[W]hen researchers look for sex differences in the brain or the mind, they are hunting a moving target. Both are in continuous interaction with the social context.”[xiii]

One of the first studies that applied the brain-sex theory to trans people (that trans people have the brains of the opposite sex) was widely criticized on neuroplasticity grounds (among other methodological problems). The study was conducted on 6 post-mortem male-to-female (MtF) transsexuals (their term) and found that a portion of the subject’s hypothalamus (the BSTc) was, on average, smaller than other genetic males. The researchers concluded that the subjects, biological males, had “a female brain structure.”[xiv] Despite the very low sample size and the problems that come with working on cadavers, the conclusions ran up against the problem of neuroplasticity.[xv] After all, the subjects had taken cross-sex hormones, had contracted HIV/AIDS, and had lived for years as the gender they had identified with—all of which may affect the brain. Most researchers believe that the credibility of the study has been severely compromised (though see below).[xvi]

Anyway, if there are male/female brain difference, we’d have to run them through a rigorous nature vs. nurture evaluation to see if neuroplasticity might account for the difference.

The third problem is that brain research is still in its infancy and technology is still developing. This is so widely recognized and agreed upon that we hardly need to belabor the point. “[N]euroscience, as a method for studying the mind, is still in its infancy,” writes Rutgers University psychologist Deena Skolnick Weisberg.[xvii] And every neuroscience researcher I’ve read agrees with this. Unfortunately, pop culture and some media reports never seem to get the memo, as they continue to make sweeping and sometimes outrageous claims based upon a single preliminary and limited study.[xviii]

It’s with much caution in our sails, then, that we venture into the open seas of research on sex differences in the brain.

Fortunately, for our purposes, we don’t need to sail very far. Aside from the fact that it’s widely disputed whether males and females come prepackaged with hardwired brain differences, even the ones who do argue for sex difference in the brain are making observations about averages not absolutes. In other words, whatever differences might exist in the brains of males and females, they are based on generalities. The brain, unlike the non-intersex body, is not sexually dimorphic. Let’s look at a few examples.

Ruben Gur is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and he’s been one to emphasize sex differences in the brain. Look at how he describes these differences:

In a stressful, confusing multi-tasking situation, women are more likely to be able to go back and forth between seeing the more logical, analytic, holistic aspects of a situation and seeing the details [while] men will be more likely to deal with [the situation] as, “I see/I do, I see/I do, I see/I do.”[xix]

Gur doesn’t say all female brains will be like this and all male brains will be that way. He says women “are more likely” to holistically analyze a particular situation. For what it’s worth, several other studies contradict Gur’s claims.[xx] But even if Gur is correct, his conclusions only prove generalities, not absolutes. There were some females who are bad at multitasking, and—like women who are six-feet tall—they fall outside the dominate pattern of how most women are. But they are still female—and so are their brains.

Susan Pinker is a developmental psychologist who advocates for sex differences in the brain. She believes that females have a thicker corpus callosum, which enables quicker left-brain and right-brain interaction. Pinker says that “men tend tomodulate their reaction to stimuli, and engage in analysis and association, whereas women tend to draw more on primary emotional reference.”[xxi] Several scholars have offered blistering critiques on the whole “sex differences in the corpus callosum” theory. In any case, even if Pinker is right and her critics are wrong, notice her language: men “tend to,” women “tend to.” Pinker is arguing for generalities.

Almost all the studies I’ve read that argue for male and female sex differences in the brain speak in terms of generalities and not absolutes:

- During sexual arousal, “men show comparatively more activity in the older, more primitive areas of the brain such as the amygdala, thalamus, and hypothalamus, while women show proportionately more activity upin the cerebral cortex.”[xxii]

- “women’s sexuality tends to be strongly linked to a close relationships…This is less true for men.”[xxiii]

- “54 percent of girls will perform above average in facial emotion processing, compared with 46 percent of boys.”[xxiv]

One of the most significant studies ever done on sex differences in the brain was just published in 2018—“Sex Differences in the Adult Human Brain: Evidence from 5,216 UK Biobank Participants.” Eighteen experts in the field teamed up to perform “the largest single-sample study of structural and functional sex differences in the human brain” by examining 2,750 females and 2,466 males (p. 2959). Specifically, the study examined “the pattern of sex differences in brain volume, surface area, cortical thickness, white matter microstructure, and functional connectivity” between adult females and males. Overall, the study found several areas of the brain where males on average differed from females. For instance, “the higher male volume…appeared largest in some regions involved in emotion and decision-making, such as the bilateral orbitofrontal cortex, the bilateral insula, and the left isthmus of the cingulate gyrus” (2969), though a few areas showed more similarities than differences between males and females (e.g. there were no sex differences in the volume of the amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, and caudate; see page 2969). If you couldn’t explain what any of this means to a 6-year-old, don’t worry, I couldn’t either. Again, I’m not claiming to be an expert in brain science. I’m only telling you what the experts are concluding, and their conclusions are always expressed in generalities—much like our stereotypes from previous posts.

Once again, the differences they found are general differences not absolute ones. The brain, in fact, is not sexually dimorphic. Though there might be differences between the averages, there is always overlap—a number of individuals who fell outside the general pattern of their sex. Or in their own words:

Overall, for every brain region that showed even large sex differences, there was always overlap between males and females, confirming that the human brain cannot—at least for the measures observed here—be described as “sexually dimorphic.”[xxv]

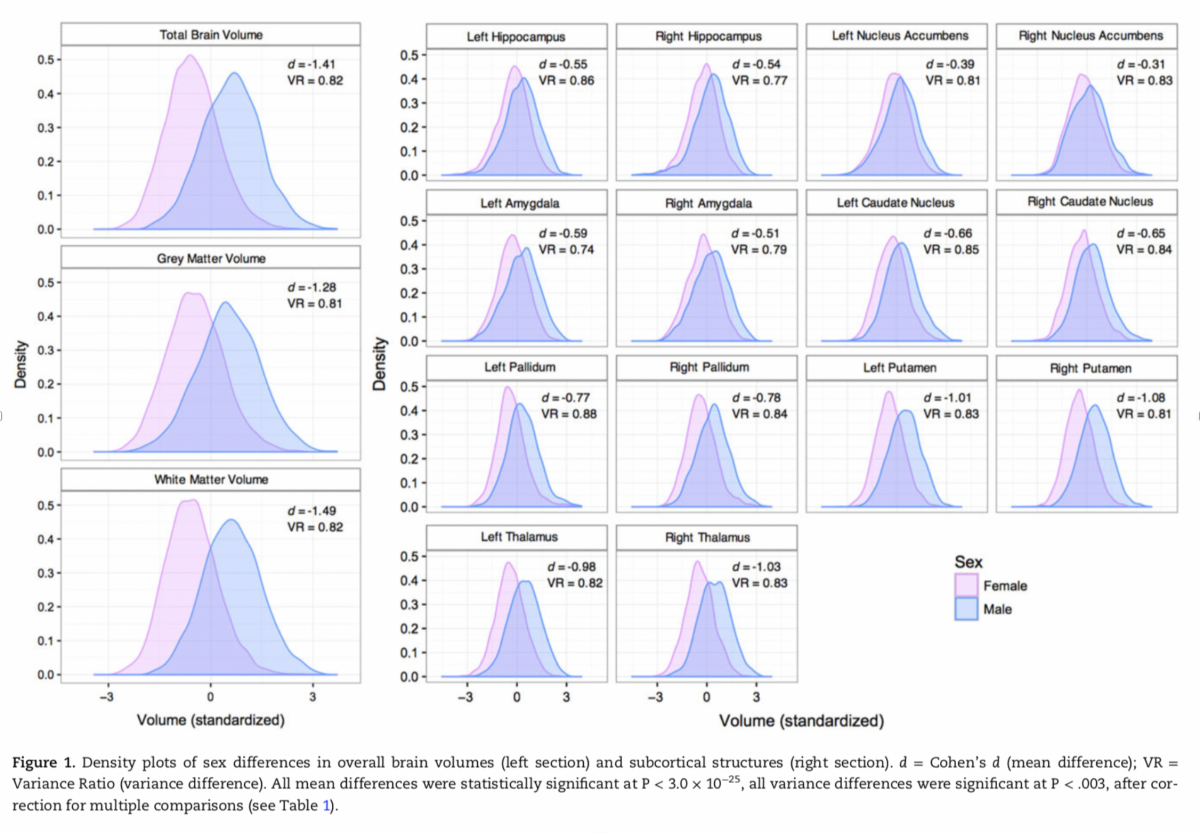

To illustrate the point, here are several graphs taken from this study. And again, this study was very eager to highlight sex differences in the brain. If there’s any confirmation bias that governed the study, it would bend toward differences not similarities. And yet this is how they mapped their findings:

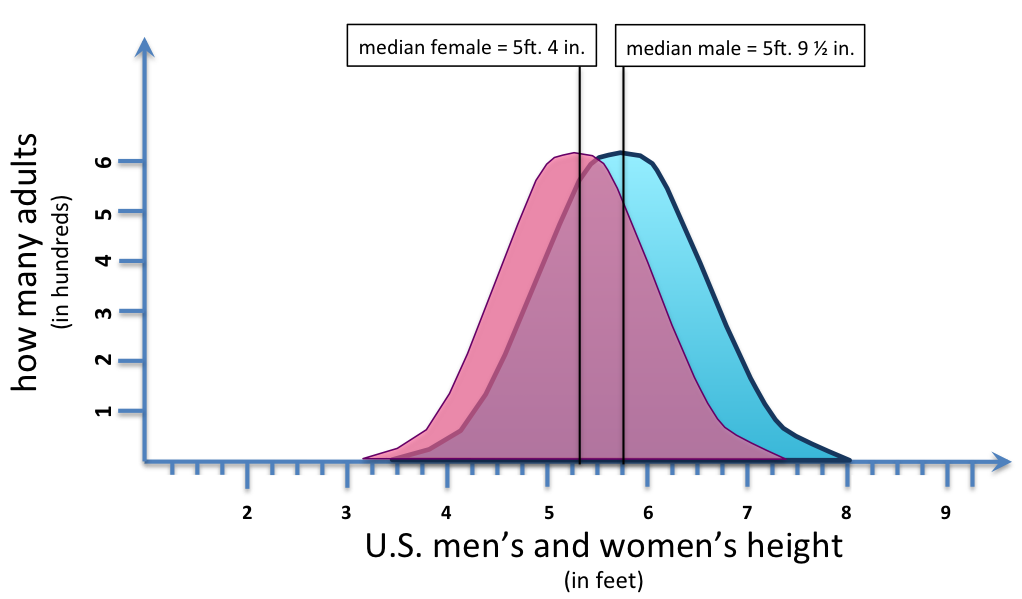

As you can see from the convenient pink and blue colors (I’ll bite my tongue), the brains of males show general differences from the brains of females, but there’s always a good deal of overlap. This is because the differences are based on averages not absolutes. In other words, the differences that (some) studies have found between males and females are similar to the differences we see, for instance, in height: [xxvi]

Most females are shorter than most males. But tall females are still females, and short males are still males, since differences in height are based on cumulative averages not absolutes. Most women are shorter than most men, most men are more aggressive than most women, and most women have more grey matter in their brains than most men. The same is not true when it comes to the biological sex of non-intersex humans. It’s not that most non-intersex men have male reproductive structures while some don’t. Biological sex, unlike brains, is sexually dimorphic in non-intersex humans.

Brain-Sex Theory, Stereotypes, and Transgender Identities

The theory that some non-intersex people have male bodies (an absolute) and female brains (a generality based on disputed scientific research) must employ gender stereotypes for this theory to work. Brains correlate with the overlapping differences between how males and females generally behave—behaviors which end up forming and nurturing cultural stereotypes. If we are going to root a person’s gender identity in the brain-sex theory, I don’t know how to do this without building a house of cards on gender stereotypes.

And yet I don’t think this dilemma has been sufficiently recognized by researchers who apply the brain-sex theory to transgender identities. For instance, Milton Diamond is a world renown professor of anatomy and reproductive biology (now retired). Perhaps he’s most famous for nearly coming to blows with the great John Money during an ongoing feud back in the 70’s over whether gender is socially constructed or biologically determined (Diamond argued for the latter; Money, the former).

But that was a long time ago. Today, Diamond is one of the foremost researchers who advocates for the brain-sex theory in the gender-identity conversation. He believes that “there seems evidence enough to consider trans persons as individuals intersexed in their brains and scant evidence to think their gender transition is a simply and unwarranted social choice.”[xxvii] One significant piece of evidence Milton cites is the Zhou, et al. study of the 6 transsexual cadavers mentioned above. And all the widely acknowledged methodological problems of that study go unmentioned by Diamond, which was honestly quite surprising to me.

In any case, Diamond goes on to argue that transgender persons have the “anatomy of one sex” but “the emotional awareness of the opposite sex.”

Wait, what? Does each sex come prepackaged with its own particular “emotional awareness?” Ask your feminist friend: “Hey, do you have a female ‘emotional awareness’?” And then duck, because you might get a combat boot thrown at you. (See, there I go with the stereotypes.) There may be a stereotype about the emotional awareness of females, and it might be based on the general patterns of female emotions, but hopefully in 2019 we’ve progressed enough to know that not all females share the same emotional awareness as the majority in the group. “The notion of a male brain and female brain fits well the popular view of men from Mars, women from Venus,” quips neuroscientist Daphna Joel, but “it does not fit scientific data.”[xxviii]

Milton’s theory is intrinsically bound up with gender stereotypes. He goes on to say: Biological females who experience “brain masculinization” will end up engaging in “male-typical behaviors.”

Male-typical behaviors? Are females who engage in “male typical behaviors” not really females? What are “male typical behaviors?” Rough and tumble play, eating fried food instead of ice-cream, and not experiencing feminine emotional awareness? You can see why feminists aren’t huge fans of the brain-sex theory and all the stereotypes that give it legs to stand on.

Milton was also fascinated that biological males who identify as female responded like typical females during the “viewing of erotic film clips.” Maybe this is because they were males with female brains. Another option is that they were just gay men.

Conclusion

Gender identity can be very complex, and I don’t claim to have all the answers about where it comes from and why some people experience a gender identity that’s incongruent with their biological sex. I do think that nature and nurture probably both play a role in causing someone to experience such incongruence, and nature may be especially strong in those who have early onset and lifelong gender dysphoria.[xxix] How much is nature? How much is nurture? It’s impossible to say.

My only point in this post is to question the scientific validity of the claim that a male could be born with a “female brain,” or vice versa. Gender incongruence could have biological roots. It probably does. But this is different from saying that a female could have a male brain. Moreover, when we root gender identity in the brain-sex theory, we run into the same problem we had with gender roles. Both are tangled up with gender stereotypes—generalities rather than absolutes.

Even if there are some sex differences in the brain, all this would show is that some females (for instance) might have stereotypically masculine behaviors, interests, and patterns of thought, but this does not mean that they have “a male brain,” since such a thing doesn’t exist. Do we really want to nurture the notion that females must embody stereotypical femininity in order to truly be a woman?

So how did I do on the male/female brain test? Not as well as I thought. Apparently, my brain is only 61% male and 39% female. I guess I shouldn’t have admitted that my favorite part of the Super Bowl is the half-time show.

[ii] R. b. Bean, “Some racial peculiarities of the negro brain,” American Journal of Anatomy 5 (1906): 353-415; cited in A. Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Body, 122.

[iii] E.g. F. P. Mall, “On several anatomical characteristics of the human brain, said to vary according to race an sex, with special reference to the frontal lobe,” American Journal of Anatomy 9 (1909): 1-32.

[iv] G.J. Romanes, “Mental differences between men and women,” in D. Spender (ed.) Education papers: Women’s quest for equality in Britain, 1850-1912 (London and New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1887/1987); cited in Fine, Delusions of Gender,140.

[v] See Fine, Delusions of Gender, 141.

[vi] Fine, Delusions of Gender,130.

[vii] In the last 50 years, more than 50,000 papers have been published on sex-differences in psychology (Daphna Joel, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYpDU040yzc). Needless to say, our discussion below won’t be able to survey all the data.

[viii] For instance, see Fine, Delusions of Gender; Jordan-Young, Brainwashed; Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Bible, ch. 5; Gina Rippon, The Gendered Brain.

[ix] You can read Demore’s original memo here: https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3914586-Googles-Ideological-Echo-Chamber.html

[x] Sex and Gender,128.

[xi] Sexing the Body, 144.

[xii] See Fine, et al. “Plasticity, plasticity plasticity…and the rigid problem of sex,” Trends in Cognitive Science 17 (2013): 550-551.

[xiii] Fine, Delusions of Gender, 236.

[xiv] Zhou, J. N., M. A. Hofman, L. J. G. Gooren, and D. F. Swaab, “Sex Difference in the Human Brain and Its Relation to Transsexuality,” Nature 378 (1995): 68-70.

[xv] The authors recognize this as a potential problem, but not everyone who cites the study does.

[xvi] See Jordan-Young, Brainstorm, 104-106;

[xvii] Cited in Fine, Delusions, 154.

[xviii] Just one recent example: https://globalnews.ca/news/4223342/transgender-brain-scan-research/

[xix] Cited in Fine, Delusions of Gender,139.

[xx] See the list and review of studies in Fine, Delusions of Gender,137-140.

[xxi] Susan Pinker, The Sexual Paradox, 116.

[xxii] Sax, Why Gender Matters, 122.

[xxiii] Letitia Anne Peplau, “Human Sexuality: How Do Men and Women Differ?” Current Directions in Psychological Science 12 (2003): 37-44, cited in Sax, 123.

[xxiv] Fine, Delusions of Gender, 159 summing up the study by Erin McClure, “A meta-analytic review of sex differences in facial expression processing and their development in infants, children, and adolescents,” Psychological Bulletin 126 (2000): 424-453.

[xxv] Stuart Ritchie, et al. “Sex Differences in the Adult Human Brain: Evidence from 5216 UK Biobank Participants,” Cerebral Cortex 28 (2018): 2959-2975. Cf. Daphna Joel, et al. “Sex Beyond the Genitalia: The Human Brain Mosaic,” PNAS 112 (2015): 15468-15473: “human brains cannot be categorized into two distinct classes: male brain/female brain.” "https://www.pnas.org/content/112/50/15468”

[xxvii] Milton Diamond, “Transsexualism as an Intersex Condition” https://www.hawaii.edu/PCSS/biblio/articles/2015to2019/2016-transsexualism.html. The dichotomy between something being hardwired in the brain versus it being a “social choice” sure seems like a false one to me. I didn’t make a “social choice” to speak English, and yet my brain isn’t hardwired to speak English instead of French. I think we could theoretically affirm that a person doesn’t choose to experience gender incongruence, and even that such incongruence is biologically shaped, but not have to believe that they have a female or intersexed brain. But that’s exactly what Milton Diamond does. He takes all the generalities we talked about above as absolutes. If a brain or behavior is more feminine, then it’s a female brain.

[xxviii] From her TEDx talk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rYpDU040yzc

[xxix] Early onset gender dysphoria can be experienced as early as 4 years old. The desistence rates of gender dysphoria will be explored in a future post. For those whose gender dysphoria is both early and lifelong, I tend to think that there are strong biological roots.

Comments

Twins

Thanks for this post. I have a son who has switch to male to female. I had talked to you in a Grand Rapids Grace//Truth conference. I appreciated your time and emotion with the subject. I know some others that are twins or know of other twins that have this similar situation, if not trans then same sex attraction. It would be interesting to see what or if being a twin has anything to do with this subject line. Again thanks for your post your studies on this subject. My son does claim that he has intersex brain. so this was quite interesting to us.

Twins, intersex brains, etc.

Hey Daniel! Good to hear from you again. Twin studies have always played a strong role in the nature/nurture conversations about SSA and gender identity. If I remember correctly, the percentage of twins where both are gay is about 50%, give or take. This shows that there probably is a strong push from nature toward SSA, especially when the twins were raised in different households or enviornemnts (rare, but it has happened). The fact that it's around 50%, however, shows that while there are biological roots, it's not genetically determined; otherwise, it'd be 100% (or close to it) not 50%.

Re: "intersex" brains. In a sense, all brains are "intersex"--a blend of stereotypically male and stereotypically female characteristics. But I think "intersex" is the wrong term here. I mean, we could say that we all have intersex hearts, lungs, brains, etc. but adding the word "intersex" could confuse the whole conversation and steal attention away from actual intersex people. The point is: there is little to no scientific evidence that brains are male or female and that someone could have a male body and a female brain, or vice versa.

However, your MtF child, probably feels like, and experiences life as if, her brain is female. I think it's important to affirm scientifically valid claims while extending much grace and copmassion to those whose deep seated life experience does not resonate with those scientific claims.

Asking the right questions

Really helpful Preston. Good to go through so many different studies and see what is being argued for. I really appreciated the graphs (yes i think the pictures were the best bit). Very interesting to see how there are generalities but not absolutes in so many areas.

Something i keep coming back to is, are we asking the right questions. We are, rightly, asking why am i the way i am, how do i understand myself? Biology has something to offer but it doesn't appear to be able, yet, to bear the weight of type of questions that come up. Am i a male who is ok being a male because i have a male brain? I was only 55% male in the quiz.

When we come to trying understanding humans, what resources can we draw on? Biology has an offer, Scripture has an offer, psychology, philosophy, experience, anthropology all have an offer. We need a holistic approach taking on board all of these (that might be the 45% coming through there). But, we'll still be left with a question about permissibility. This isn't a question of why i am the way i am so much as what can i do given how i am?

Maybe this is more of a discipleship question but as this isn't an academic topic but a person based one, we should be ending there anyway. As a male, with a 55% male brain, who is OK being a male - what is permissible for me? Is it OK for me to use my status to exert power over others? No. Make my experience the norm and standard for others? No. Perpetuate a culture that elevates that? No.

But also, is it OK for me to body build or not? Shave or not? Take hair replacement treatment or not? Have Botox? Take hormone treatment? Undergo reassignment/affirming surgery?

My body is me, and i am my body. What i have received in many defines my life experience. What i do with my body in many determines my future. What is permissible?

Identity precedes practice

Again, you're asking all the right questions! I love these:

" is it OK for me to body build or not? Shave or not? Take hair replacement treatment or not? Have Botox? Take hormone treatment? Undergo reassignment/affirming surgery?"

I promise you, this is ultimately where I want to end up. But I think we need to lay a thick foundation of theological anthropology so that we'll be in a solid place to answer those questions.

Body and identity

Agreed that we need a 'thick foundation of theological anthropology'. 'Identity precedes practice' is a good summary.

On Gender Dysphoria and Children

Thank you for this interesting series.

You may find the articles in the following links useful:

http://gdworkinggroup.org/2019/08/02/gender-dysphoria-resource-for-provi...?

http://gdworkinggroup.org/2019/08/09/key-issues-in-decision-making-for-g...?

Also - I did my postgraduate study with Milton Diamond in 1980

Thanks!

Wow, you studied with Milton! That's awesome! Thanks for the articles.

Gender identity

The heart is treated differently for males and females as men and women have different experiences of chest pain. The current healthcare guidelines for Troponin level is different for men and women. Will a biological male who's gender identity is "female" have a male heart or a female heart for treatment of Troponin level?

feminists versus trans

Hi Preston,

Another helpful and lucid article. Your conclusion that assertions of male or female brains can only be based in gender stereotyping highlights some of the ideological stakes in this discussion. At several points you rhetorically buttress your argument by highlighting trans v. feminist tensions, which has become pretty explosive within LGBTQ+ communities, e.g. “trans-exclusionary radical feminists.” But I would caution against invoking that feminist v. trans debate as support for your argument. Although it does epitomize your point, I think it might undermine some readers’ trust if you are perceived as taking taking sides in that other debate or as “using” feminists to challenge trans folks. Furthermore, some TERFs have taken up common cause with some Christians to legislate against trans rights, and I don’t think you want to be associated with those campaigns.

brain structure v. brain activity

The brain studies you cite analyze and compare the size and shape of brain structures in male and female brains. But our experience of our minds - thinking, feeling, etc. - is neural activity not structure alone. Might patterns of neural activity be more salient to male v. female investigation? The advent of fMRI technology has enabled scientific leaps in analyzing brain function. I’d be surprised if that has not been deployed in brain-sex research.