The following blog is written by Greg Coles. Greg is a Ph.D. candidate at Penn State and is part of The Center's collaboration team.

My favorite online dictionary has a search bar bearing the default phrase, “I’m searching for...” So when I went online a few days ago to look up the etymology of the word “intimacy,” I found myself brazenly declaring to my web browser, “I’m searching for... intimacy.”

As I hit Enter, Johnny Lee’s song about lookin’ for love in all the wrong places came to mind. The online dictionary, bless its HTML-coded heart and its five hundred thousand reliable entries, didn’t do much to satisfy my deepest longings.

The search for intimacy is central to our identity as human beings. And yet our pursuit of it so often feels perfunctory, no more thought through than if we’d typed it into our dictionary search bar, hit Enter, and prayed for the best. We assume that intimacy will come as the byproduct of more tangible things: friendship, family, sex. When we find it in those things, we thrive—and when we don’t find it, we glut ourselves on the very things that have failed us, pouring water into our porous souls and wondering why we stay empty.

The decision to live as a celibate gay Christian is a weighty one in part because it means rejecting society’s most obvious pathways to intimacy. The vision of familial intimacy so celebrated in the evangelical church, the vision of sexual intimacy between spouses—these aren’t available to someone like me. I’m left in many ways to fend for myself, to piece together a patchwork quilt of intimacy by relying on friendship alone.

But even friendship can feel like a catch-22 when you’re gay in the church. The fear of damaging your friendships, or of changing them irreparably, can make you hold your tongue about your sexuality. And yet, as long as you hide yourself away from everyone, you’ll never feel truly known. You’ll always fall short of the kind of intimacy you long for.

The human impulse to get naked with another human being is certainly sexual in nature, but it’s also so much more than sexual. It’s about having every facet of yourself known, every crack and curve. It’s about having nothing left to hide. As a closeted gay person, you risk losing both kinds of nakedness at once, denying yourself emotional intimacy in the same breath that you deny sexual intimacy.

Living without sex is difficult. Living without intimacy is a death sentence.

I’ve lost count now of how many times over the years I’ve come out to friends and family members. But it never gets any easier. I stammer over my words, say everything poorly, forget important details and include meaningless ones. Despite what my third grade soccer coach promised, practice does not necessarily make perfect. (Incidentally, my soccer skills are also a testament to the failure of this aphorism.)

For me, the strangest part of coming out is the demand it places on the people I confide in. It has always seemed brutally unfair to unload my burden onto others, to drag them against their will into an intimate confidence. I’ve always feared being the over-sharer, like the guy in your small group who gives gruesome details about his foot fungus or his erectile dysfunction. I’m afraid of telling people information they neither needed nor wanted to hear. And sadly, there’s no way of checking in advance whether people want to be privy to your secret. (“Let’s say, hypothetically, if I were gay, would you want me to tell you?”) You can only take a wild guess and then hope for the best when you open your mouth.

Sometimes, of course, people will ask you questions that make it almost impossible not to come out to them. But even those questions usually aren’t meant to inspire such intimate self-disclosure. Coming out as gay every time someone asks your thoughts on homosexuality, or every time someone asks what made your week challenging, is a bit like stripping naked every time someone asks to see your tattoo.

….

“Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.” In 1 Corinthians 13, Paul makes this promise to himself and his readers in Corinth. It’s his way of coping with the unknown, the unanswered, the mysteries of God. Paul, too, had thorns in his flesh, fracture lines on his heart, reasons to shake his fist at the sky. Paul, too, needed a promise stronger than a lifetime of uncertainty.

It’s a two-part promise, really. First of all, that the answers do exist, that they’re coming someday. That a perfect God has numbered every hair on our heads and declared us part of his very good creation. It’s a promise that we’ll know.

But second, and maybe more importantly, it’s a promise for the meantime, in the midst of the unknowing. It’s a promise that we are fully seen, fully known, fully loved. Our limitations don’t limit heaven. As Hamlet tells us, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” The partiality of our knowledge is no threat to sovereignty of God.

When I allow myself to be known—when I tell the most baffling parts of my story to trusted friends and encounter their unconditional love in return—I begin to understand the love of God. A love that knows me fully. A love that, when I feel too weak to hold onto it, is strong enough to hold me instead.

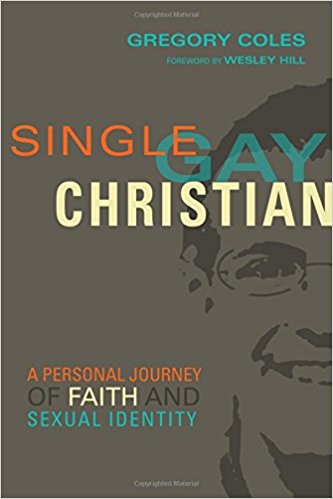

The previous blog is an excerpt from Greg Coles' forthcoming book: Single, Gay, Christian: A Personal Journey of Faith and Sexual Identity (InterVarsity Press, 2017). Used with permission.